Artists

Ts̱ēmā Igharas

Ts̱ēmā Igharas (Tāłtān, born in Smithers, Canada; lives in Vancouver, Canada) delves into the connection between bodies and the land, and challenges extractivism-related issues through Indigenous resistance strategies and methodologies. Her works are often articulated around interventions made directly on the land—either by her or by corporate mining industries. Casting a sensitive and critical gaze on materials, she offers narratives in which natural resources have their say.

- Born

- Smithers, Canada

- Countries / Nations

- Tāłtān, Canada

- Lives

- Vancouver, Canada

- Website

- tsema.ca

Works

Ts̱ēmā Igharas and Erin Siddall, Port Radium Mine Rock, 2019, silk prints. Commissioned by MOMENTA Biennale de l’image and the Toronto Biennial of Art. Courtesy of the artists © Erin Siddall

Ts̱ēmā Igharas and Erin Siddall, Port Radium Mine Rock, 2019, silk prints. Commissioned by MOMENTA Biennale de l’image and the Toronto Biennial of Art. Courtesy of the artists © Erin Siddall

Ts̱ēmā Igharas and Erin Siddall, A Money Rock, 2019, photograph. Commissioned by MOMENTA Biennale de l’image and the Toronto Biennial of Art. Courtesy of the artists

Ts̱ēmā Igharas and Erin Siddall, Great Bear Lake, 2019, photograph. Commissioned by MOMENTA Biennale de l’image and the Toronto Biennial of Art. Courtesy of the artists

Ts̱ēmā Igharas, Emergence 1, 2016, digital photograph. Courtesy of the artist

Tsēmā Igharas, Emergence, augmented reality artwork documentation, 2021.

Of the Land

Great Bear Money Rock is part of a larger research project being conducted by Ts̱ēmā and Siddall on Port Radium, an abandoned mine near Great Bear Lake, in the Northwest Territories. The Dene community living on the lake’s shore is still feeling the effects of the radiation emitted by uranium extracted from the mine, which has been officially closed since 1982. In 2019, Ts̱ēmā and Siddall went to Délı̨nę, in the Sahtu Region—265 kilometres away from the mine—and gathered material, audio, and visual elements, laying the groundwork for the project. In two thematic parts, one at the Galerie de l’UQAM and the other at VOX, Great Bear Money Rock traces how the land and the life of local Indigenous communities overlap. At the Galerie de l’UQAM, the installation Great Bear Lake is the Boss is composed of a garden of crystals from the site of the mine, enclosed in glass bubbles to contain the weak radioactivity that they emit. Even though the glass is fragile, it plays a doubly protective role: it keeps us from contact with the ore, and it preserves the territory in its translucent showcase—territory threatened by human activity. Large-format prints placed on rock structures show the heaps of stones that cover the abandoned mine. Archived by Ts̱ēmā and Siddall during their crossing of Great Bear Lake, audio recordings inundate these rubbly landscapes. Retracing the narratives conserved in the waters of the lake and in the rocks strewn around the landscape, Great Bear Money Rock exhibitses the imperceptible, that which evades our senses but whose effects are nonetheless profoundly physical.

In collaboration with the Toronto Biennial of Art

Wet Futures

At VOX, the installation The Lake is a Cup considers the memory properties of water. Shot by Ts̱ēmā and Siddall, views of the ghost mine, Délı̨nę, and the lake are splintered by projection through a water bottle balanced on a long, narrow prism. Like water, but also like bodies, the film accumulates radioactivity. The installation is permeated by the mechanical sounds made by the projector in an almost-organic cadence that constantly brings us back to our own bodies. Retracing the narratives conserved in the waters of the lake and in the rocks strewn around the landscape, Great Bear Money Rock exhibitses the imperceptible, that which evades our senses but whose effects are nonetheless profoundly physical.

In collaboration with the Toronto Biennial of Art

Liquid Crystals

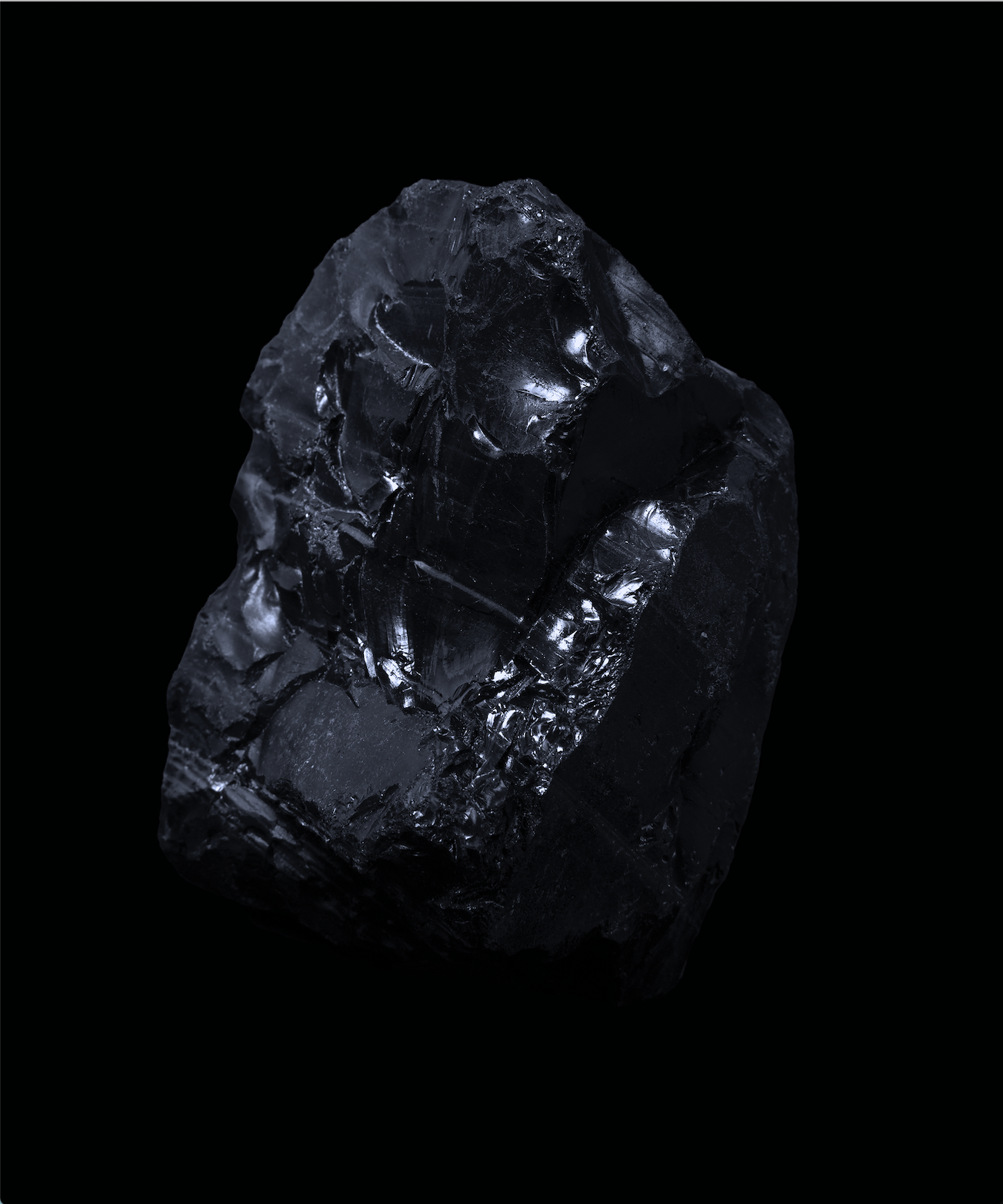

In Emergence, Ts̱ēmā features specimens of obsidian from Mount Edziza, situated in what is now known as northwest British Columbia in the Ancestral territory of the Tāłtān people, to which she belongs. A silica-rich volcanic rock, obsidian has a particular significance for Ts̱ēmā, as it bears the vitrified memory of her ancestors, their way of life, and their material culture. Indeed, obsidian was in widespread use in these lands well before European colonization: a valuable trade item, it was used in crafts and to make tools and weapons. Prized for its hardness, strength, and unique glossy look, the precious mineral was mined in the region for thousands of years. In Emergence, Ts̱ēmā probes the aesthetic properties of the obsidian, which varies widely in colour depending on its mineralogical composition. In the form of an installation, portraits of obsidian are combined with urban landscapes to tell a complex human and geological story reflecting at once the Indigenous, colonial, and capitalist heritages contained within the stone. The ghostly presence of the striking and enigmatic sculptural masses—streaked with iridescent shards and sharply contoured—operates as a sublime spectre arising from time immemorial. The work draws on the mineral’s power of attraction over humans, as its appearance, oscillating between rock and glass, lends it the aura of a mysterious being. After all, its very existence results from an incredible encounter between two antagonistic matters: the collision, during a volcanic eruption, of hot lava and masses of ice.